Pink has been a girl’s colour for about seventy or eighty years. Since the blue-for-boys/pink-for-girls thing has been taken up with such aplomb and vigour by marketers of gendered products, primarily toys and clothes, and since people tend to be painfully ignorant of times other than those they live in, there is a contemporary debate about whether the pink-for-girls/blue-for-boys dichotomy is learned or innate. The very existence of this debate is an embarrassment for anyone who knows anything about anything, but it does provide a good example of how science writers in the popular media tend to skew the results of scientific studies so that they appear to provide support for culturally produced norms or biases. So here it is.

The paper “Biological components of sex differences in color preference” appeared in the August 2007 issue of Current Biology, and is thankfully available in full here. The two researchers involved with this study did a cross-cultural comparison of colour preferences among 208 participants, 171 of which were British caucasian, and 27 of which were mainland Han Chinese. The two groups were roughly split in half by gender. The study involved a simple forced-choice rapid paired-comparison task, where participants were shown two colours on a screen and were asked to select the one they preferred as quickly as possible using a mouse cursor. These were the results:

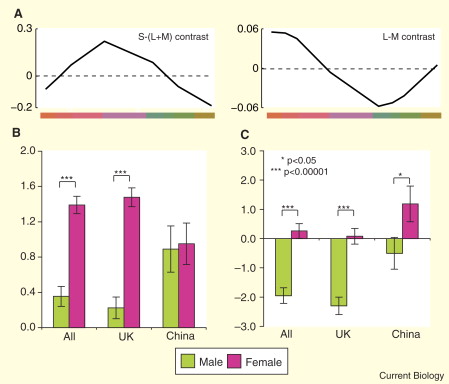

The two graphs on the bottom, B and C, represent the two sets of tests they did that targeted different contrast-pairs based on the cones in the retina–test B represents the S vs. L and M cones, or blue-yellow contrast, and C represents the L vs. M cones, or red-green contrast. As the graphs show, all participants preferred blue on the blue-yellow test, although men preferred it more, and women preferred red on the red-green test, whereas men preferred green. Keep in mind that these weren’t solid primary colours that were used in the tests, but were rather ranges of hues that were weighted according to the contrast pairs – in other words, women preferred reddish blues overall, whereas men preferred greenish blues.

Note that these results reflect the well-researched phenomenon of male colourblindness, which is something like 10 times greater in the male population than in the female population. The researchers cite two possible causes for these results, based on the possibility that this sex difference is an adaptation: first, women may have evolved the ability to distinguish reds from greens because they were the gatherers and they needed the ability to distinguish fruits from foliage, whereas making subtle colour distinctions was not as necessary for men, who were the hunters. Second, women may have evolved the ability to distinguish subtle shades of red in order to recognize flushed faces, which was necessary to fulfill their role as nurturing caregivers.

The second explanation seems like bunk, to use the parlance of our times. A study that showed a group of men and women flushed faces and demonstrated that men were less able to distinguish them from regular faces might give this theory more credence, but until then it seems like pure speculation. The second explanation makes sense, assuming that we have reliable data somewhere that indicates women were the gatherers while men were out hunting (I am by no means an anthropologist). Trichromacy would be a very useful adaptation if reddish fruits and vegetables were a big part of our diet, and females would evolve better colour vision if finding those fruits and veggies was their job. However well paleoanthropology explains trichromacy, though, I am not clear from reading the paper how preference for reddish colours is based on the ability to distinguish reddish colours. If I conceded that women are more likely to be trichromatic because of the evolutionary explanation, it would not follow that they like reddish colours more just because they can distinguish them. If they indicated a preference because “red” indicates “food,” then why wouldn’t men with normal colour vision register the same preference? Indeed, even in the case of the bunk explanation, reddish colours may well be associated with distress, which would make them less preferable. The point I’m trying to make is not that either theory is more or less correct, but that neither theory does even a half-assed job of explaining the results, so it’s tempting to look at the proffered explanations as being heavily biased.

Compared to the article in Time, though, the research paper is a work of extreme sensitivity. The Time article overlooks the dubious link between the article’s data and its explanation, and frames the whole thing as if the study were proof that women inherently like pink more than blue. Nevermind that the study had very little to do with pink, or that the study said more about preferences for red and green than about pink and blue; the Times saw an opportunity to reinforce their previously held assumptions under the guise of science, and they went for it. It’s unfortunate, then, that although they did a surprisingly good job of summarizing the article, the message that they ended up getting across had less to do with the study itself than it did with Time’s biases. Their caveat near the beginning,

women may be biologically programmed to prefer the color pink — or, at least, redder shades of blue — more than men

(emphasis added) ends up drowned under the headline just above it that proclaims definitively that the study explains “Why Girls Like Pink.” As Kapitano once said with regard to Neuroskeptic, “To be well informed about science, ignore everything you read about it in newspapers. Then read some science books if you like, but ignoring journalists is the important thing.”